While there has been plenty of fictions circling the dystopian possibility of machine learning leading to artificial intelligence (AI) robots taking over our society – smart technologies employed by the government and police forces in the future to monitor and surveil the citizens – not many discuss a more imminent and troubling issue arising in the field: that is, bigotry.

Why would machines be prejudiced? After all, aren’t they programmable and, supposedly, impartial blank slates? Sadly, the answer is because of us, humans. As machine learning is a program that picks up any information available in its environment – and absorbs whatever input fed to it by the users – it does not distinguish between discriminatory and non-discriminatory content, but instead draws conclusions and solves problem-based on existing data.

Indeed, the surprisingly ironic truth reveals that “robots have been racist and sexist for as long as the people who created them have been racist and sexist, because machines can work only from the information given to them, usually by the white, straight men who dominate the fields of technology and robotics.” In other words, it is not AI who is bigoted, but rather us: “We’re prejudiced and that AI is learning it,” Joanna Bryson, a computer scientist at the University of Bath and a co-author, explained.

For many people, including myself, machines and robots have long been regarded as objective, ‘mindless’ technologies that process and analyze information, obey the user’s commands and execute actions the way they are programmed. They are merely agencies, designed to be operated. However, some movies have approached them in a very different way – by humanizing them. For example, Chappie (2015) depicts an AI robot that was programmed to think with emotions and having opinions (like any human being). In the trailer, Chappie uttered a few lines that were both powerful and thought-provoking: “I’m consciousness. I’m alive. I’m Chappie.” The use of “consciousness” and “alive” in conjunction symbolically gestured the possibility of machines sharing human’s psychological and physical capacities; the AI robot possesses a mind that allows it to sense its world and self-proclaims its identity as Chappie.

Through anthropomorphizing robots, we can actually better understand why the problem of sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination and hatred exist among robots. Robots are not perfect as much as we would like to think so. As AI programs – ranging from Google Translate to criminal justice system’s risk assessment – are getting closer to acquiring human-like language and cognitive abilities, they are also absorbing the deeply ingrained prejudices masked by the patterns of language use. Just as one of the characters proclaimed in Chappie’s trailer, “[the robot is] like a child. It has to learn.” AI programs develop its vocabulary base via how often the terms show up together in existing sources, build word associations like “father:doctor :: mother:nurse”, and learn to perceive the world through its acquired information, thus a biased view.

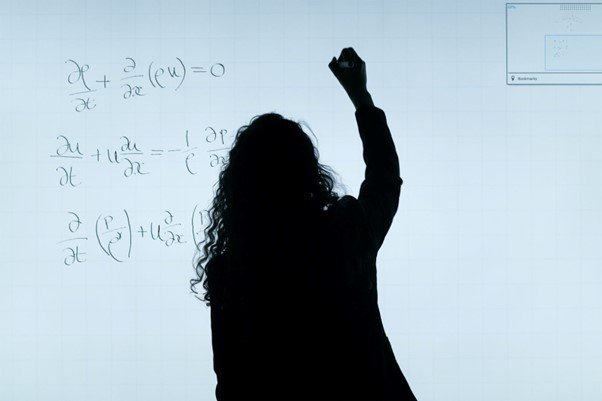

Returning to this blog post’s headline question – “Is machine learning or AI sexist?” – my answer is both yes and no. ‘Yes’ because sexist and racist problems alike are exhibited across many cases from Google’s word2vec and Microsoft’s infamous AI bot, Tay. And ‘No’ because the problem is not rooted in the robots, but people – the computer scientists who (unconsciously) perpetuate their own thinking and beliefs when designing the programs; the users who taught Tay to speak in racist, sexist languages and abused its vulnerability; and the societies that still hold certain supremacist beliefs and debunk equality. If we cannot overcome our own biases, how can we simply assume or expect technologies to fix these issues for us?

Tabitha wrote in her blog post that the inclusion and encouragement of inviting more women to the AI field is a requisite for combating the problem, for the ‘us’ in “teaching machines to think like us all” is indispensable. I cannot agree with her more. We need to realize that technologies will not be the entire solution to the problems existing in our world, but rather a tool that requires our guidance and actions to achieve the better world we hope for. We also need to bear in mind that because technologies are not entirely impartial, it is necessary that we not forget our own judgments, for our thinking goes beyond algorithms and involves ethics, sense of justice, feelings like empathy and compassion, and other elements computers have yet to learn.

About the author

A recent graduate of New York University, Vivien Li is a global storyteller, curious traveler, and aspiring foodie. Growing up with a bicultural background (Taiwanese and American), she is deeply passionate about learning about cultures across the world and spent 4 semesters studying away: from London, Washington DC to Prague. With a major in Media, Culture and Communication and interests in technology and business, Vivien enjoys listening to, sharing, and voicing ideas of her own and from different people, and hopes to bring positive impact through her work and writing—starting with SheCanCode.